Timeline

Archaeologists divide the past into time periods based on shared cultural traits, as a way to understand the ever-changing nature of life here. These time periods are defined by cultural trends, for instance the technology that we use, the clothes that we wear, the art that we create, and the food that we eat. Ancestral peoples experienced and created these same cultural trends in how they made their tools, the designs that they painted on pottery, and even what they ate.

In southeast New Mexico the Paleoindian period, the Archaic period, the Formative period, and the Protohistoric/Historic period have been defined by archaeologists. Learn more about each one below.

As you read about these periods in the past, it is important to know that Indigenous peoples have lived on this landscape since time immemorial. This means that people have lived here longer than we can remember, and longer than we can assign a definition to. These ancestors may not have left behind any signs of their lives, but their descendants know who they were. Their presence is known by the lineage that they created, by the contemporary Indigenous communities that remain here today.

Paleoindian Period 10,000-5,500 B.C.

Until recently the earliest archaeologically known human occupation in southeast New Mexico was around 11,500 B.C. However, new archaeological evidence from White Sands National Park places people in the region at least 21,000-23,000 years ago. Fossilized footprints show us that men, women, and children lived here long before the Paleoindian period. Beyond their lasting footprints, though, there is little to no evidence of these early humans. Significant evidence of humans on the landscape begins in the Paleoindian period.

The Paleoindian period encompasses a 5,500-year span between 10,000 and 5,500 B.C. Throughout this period ancestral peoples were highly mobile on the landscape, meaning that they moved frequently, typically following food and water sources. Our understanding of their reliance on plants as a food source is sparse, but we do know that they hunted and ate large mammals called megafauna. Now extinct, these megafauna included mammoth, mastodon, and bison. Hunters used large, stone spear points to hunt these enormous creatures, and these tools dominate the archaeological record. Towards the end of the Paleoindian period (about 10,000 years ago) the climate in southeast New Mexico became drier, making water sources less abundant. With this environmental change came a shift in lifestyle for ancestral nomads. As megafauna went extinct, they focused their hunting on bison and adopted a more diverse diet that included more plants.

Archaic Period 5,500 B.C.-A.D. 500

Moving into the Archaic period, the climate continued to warm. The beginning of this period is marked by a series of adaptations. Ancestral peoples included a range of new animals and plants in their diet, which changed the tools that they made and used. Smaller projectile points and plant processing grinding stones begin to appear in the archaeological record at the beginning of the Archaic period. Movement patterns also changed as ancestral peoples moved further north towards reliable water sources.

The newfound reliance on plants also meant that groups could stay in one place for longer periods and they began to establish seasonal settlements. In the latter half of this period, some archaic peoples began living in larger villages and participating in communal food procuring and processing. The first dateable rock art also appears throughout the late Archaic period. It is clear that throughout this period people are creating new kinds of social networks with their neighbors and connections to the landscape around them. By the late Archaic period communities are building permanent houses, large-scale storage facilities, and significant refuse piles. These features suggest that some groups were growing in size and becoming less mobile.

Formative Period A.D. 500-1375

Next came the Formative period, defined by the presence of the bow and arrow and the introduction of ceramics. Prior to this period ancestral peoples relied on woven basketry to serve as bowls, plates, cups, and jars, until they began using clay from the earth to make undecorated pottery around A.D. 500. During this period in southeast New Mexico, people continued to be highly mobile on the landscape, again moving with water and food sources throughout the year. During the late Formative period ancestral peoples began producing decorated ceramics, and by the late 14th century more permanent villages were popping up. Interestingly, some villages, like Fox Place, included communal buildings, like kivas. Kivas are used extensively by Pueblo peoples in northern New Mexico. Their presence in the south suggests that some Pueblo peoples may have migrated south and brought their architectural plans with them.

People, traditions, food, and products were highly mobile throughout this time. Entire groups of people were migrating and intermixing with populations from outside of the region, and they brought with them their religion, traditions, technology, food, and knowledge. During this period the archaeological record reflects a variety of nonlocal lithic materials, tool forms and ceramic designs, domesticated plants, and foreign animal products. For a short time, southeast New Mexico was a bustling region that connected the Pueblos to the north and west, and the Plains peoples to the east.

Proto-historic/Historic A.D. 1375-Present

The Proto-historic and Historic periods span from A.D. 1375 to the present day. Around A.D. 1450 a widespread depopulation of settlements in southeast New Mexico took place. The historic period is marked by the arrival of Spaniards throughout the 1500’s. Historic records tell us that colonizers encountered the Apache and Jumano peoples as they traveled through southeast New Mexico.

How long ago was 1,000 B.C.

Wondering how to decipher timeline terminology? Keep reading to learn more about B.C., B.C.E., A.D., and C.E.

When learning about people, places, or things in the past, you’ll often see years marked by either B.C., B.C.E, A.D., or C.E. In this section we’ll help you decipher what these markers mean and how to use them.

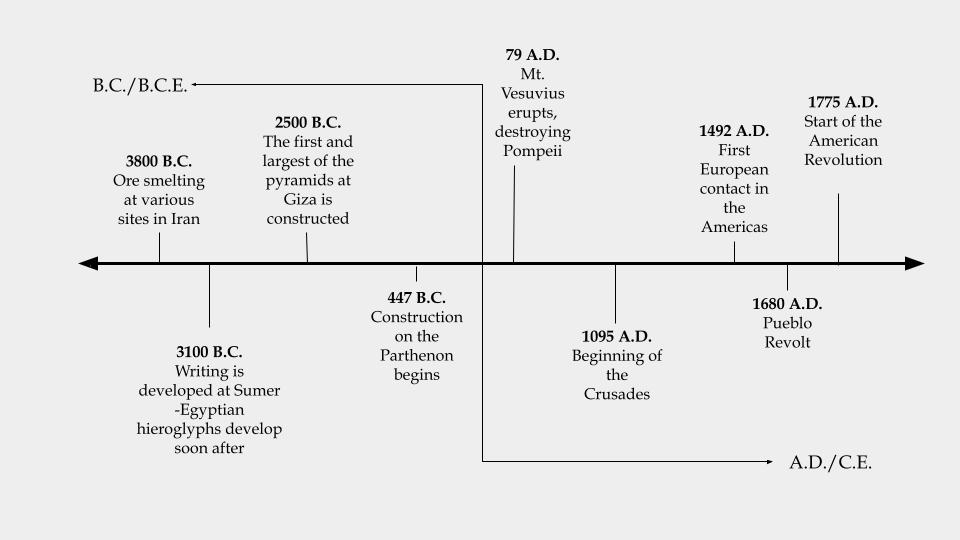

If you look at the timeline, you’ll see that B.C./B.C.E and A.D./C.E. are divided in the middle of the timeline. This division marks year 1. Everything that came before year one is defined as either B.C. or B.C.E, and everything that comes after is defined as either A.D. or C.E. Although we don’t often use these markers when we write out historic or modern dates, we currently live in the A.D./C.E. era. For instance, the year 2022 could also be written as A.D. 2022.

First, let’s look at the terms B.C. and B.C.E.. B.C. means “Before Christ” while B.C.E. means “Before Common Era.” These terms are often used interchangeably and both refer to the period before year one. If you look at the example timeline above, you’ll notice that B.C. and B.C.E dates go backwards from one. So, the year 1,500 is older than the year 1.

The terms A.D. and C.E. work in much the same way. A.D. means “Anno Domini” or “in the year of the Lord” while C.E. means “Common Era.” A.D. and C.E. count up from year one. So year 1 is older than the year 2022. While B.C. and B.C.E count backwards from one, A.D. and C.E. count forwards.