Subsistence

When was the last time you ate? For most of us, it was probably within a few hours. Everybody eats, but we all do it in different ways. Subsistence, the ways that a group selects, obtains, and prepares foods and medicines, is central to how archaeologists think about people in the past and their daily and seasonal lives.

When was the last time you ate? For most of us, it was probably within a few hours. Everybody eats, but we all do it in different ways. Subsistence, the ways that a group selects, obtains, and prepares foods and medicines, is central to how archaeologists think about people in the past and their daily and seasonal lives.

We can think about the primary way people get their important foods as one of the most important aspects defining their life as a community. Within the southeast of New Mexico, there is a history of communities who foraged, gardened, tended to wild plants and animals, or farmed, with many peoples drawing on all of these practices. Let’s take a look at these strategies.

Hunting and Gathering

In the past, communities had a more variable idea about where they lived, or how long they lived there. Hunters and gatherers were typically nomadic, meaning that they moved from place to place frequently, usually following resources (like native plants, animals, and water) as the seasons changed. This type of settlement pattern, moving from place to place, was common prior to agricultural development and for those who did not adopt agriculture. Because they don’t store foods like grain and bean crops, foragers need to ensure that everyone in the group can survive off of a smaller amount of local, often in-season, resources. As a result, hunters and gatherers in the past lived in small family units.

Understanding how societies get their food helps archaeologists answer questions like:

What were people in the past eating?

Who were they trading with and what were they trading?

Did people live in highly mobile groups or were they sedentary?

How many people could each subsistence strategy support? How big were individual groups?

Were groups made up of one or multiple nuclear or extended families?

What were the societal roles of the group members?

Because these groups were small and moved frequently, they typically established hunting camps and settlement camps. An important aspect of foraging subsistence is the ability to live, travel, and hunt effectively as a group. You may have heard that only men hunted while women gathered. This is a common misconception about nomadic foragers. Although some groups in the past may have organized themselves in this way, it is more likely that all fit members of the group participated in both activities while children and older members stayed behind at camp.

Nomadic peoples who moved frequently across the land left unique cultural footprints. As a result of their highly mobile way of life, these groups tend to create small, job specific sites. Imagine what life would be like if you had to carry nearly all your tools, clothes, and daily needs with you. You would probably choose to rely on objects that could serve a number of purposes, the same choice many early foragers made. However, without a single place to do everything year-round, more nomadic communities could select the best kind of camp for different purposes. Slaughtering an animal might create the need for specific camp set-ups and the remains discarded tell us what happened there. Drying fruits or weaving baskets in the spring would create a distinct set of needs and leave a different archaeological pattern.

Other distinctive tasks that left behind unique sites include buffalo hunting, agave roasting, and quarrying rocks for stone tools.

Horticulture

Horticultural societies depend on local gardens as a primary food source. Sometimes horticulturists in the past lived sedentary or semi-sedentary lives, in which they settled in one or more places for months at a time. These groups typically establish residential camps or village sites. One defining element of horticulture is the unique approach to planting and harvesting crops. Not only is horticulture practiced on a much smaller scale than agriculture, but horticultural groups also use a rotating-field approach to planting. Instead of harvesting from the same plot of land year after year, horticulturalists change the fields that they use every couple of years, which allows depleted soils to become enriched again by the natural overgrowth of plants. At the end of a 5-10 year period, these overgrown fields are cleared using a slash-and-burn method and crops are re-planted.

The introduction of food sources scheduled, located, and controlled by people affects the carrying-capacity of the land. Carrying capacity refers to the number of humans or animals that a region can live off the land without depleting resources like food and water. Cultivating plants results in a larger carrying-capacity for the land.

Have you ever planted your own garden?

Instead of driving to the supermarket to find food, you can harvest fruits and vegetables from your own yard. The same process was true in the past. Some groups in the past began planting foods in places that they lived, which then provided more nutrition and may have even resulted in a food surplus.

Although horticulturalists can rely on foods from their gardens, they must also continue to forage and hunt in order to retain a balanced diet, and to support the larger populations.

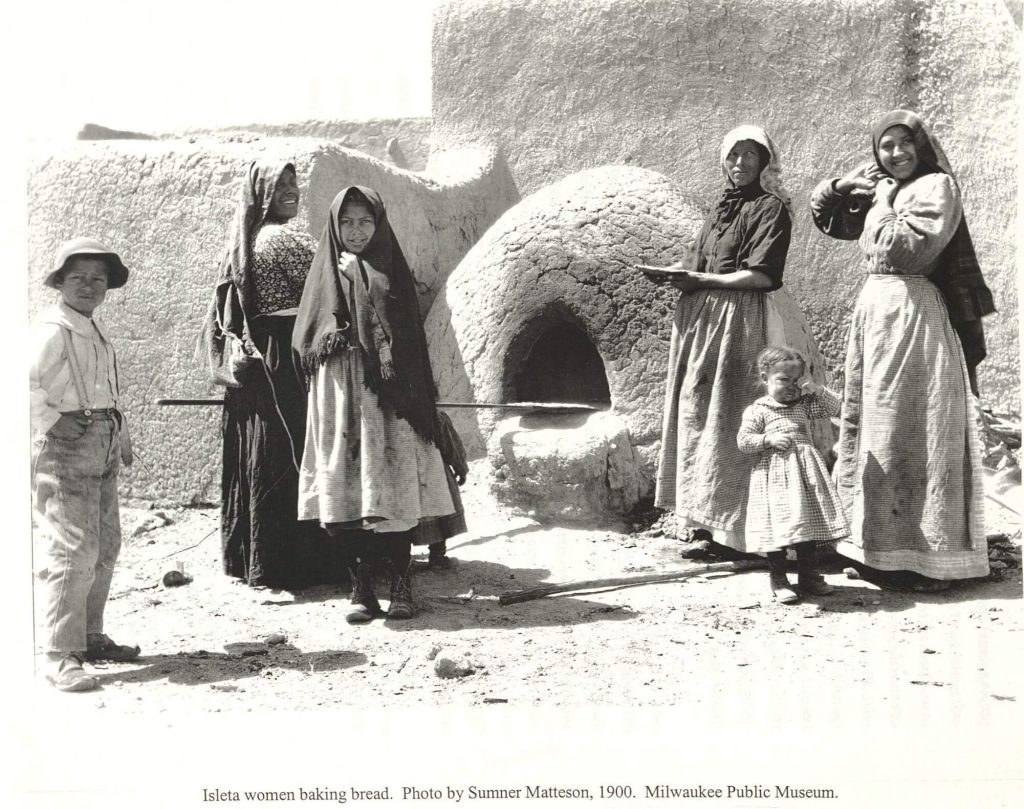

Evidence of horticultural populations often comes from residue analysis of stone tools, ground stone, and pottery. Often, undisturbed artifacts will retain small traces of plant matter that rubbed off when tools were used to cut, grind, cook, or serve these plants. When we find traces of cultivated plants, like maize, at archaeological sites it tells us that peoples at these sites grew or traded for these crops. We also rely on clues like the size, layout, and length of settlement, kinds of artifacts, and oral histories to help us understand how people were relating to local plants.

Agriculture

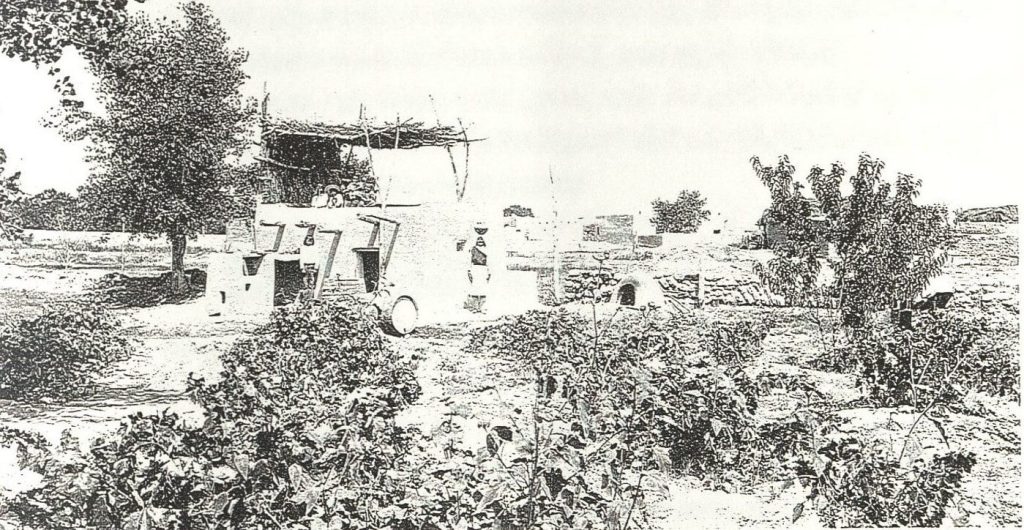

Agrarian societies, or communities who rely on cultivated crops as their primary food source, are uncommon in prehistoric southeast New Mexico. Agriculturalists live exclusively in sedentary village sites, a necessity in order to plant, tend, and harvest crops at a larger scale. Although the primary food source for these groups comes from crops, the necessity to hunt and gather remains. Similarly to horticulture societies, past agriculturists also employed hunting groups to venture out and establish small hunting camps as well. Some agricultural groups may have hunted their own meat, while others may have traded surplus from crops for dried meats. Unlike hunters and gatherers or even horticulturists, communities who relied on agriculture in the past were at a higher risk of malnutrition or famine. Hunters and gatherers who moved with the seasons could easily adapt and find food where it was flourishing, even when bad weather meant certain plants or animals weren’t available. For peoples who rely largely on one food source, like crops, bad weather can mean a failed crop and severe food shortages. Hunters and gatherers also ate a diverse diet, whereas agriculturists in the past were susceptible to malnutrition when they relied too heavily on their crops.

In comparison to horticulturalists, agrarian villages grow large scale crops with the intent to feed a large community of hundreds or thousands of members. Because agriculture can support many more people, these communities also practice job specialization, meaning that individuals have specific tasks like farming, pottery making, or food processing. This is a contrast to hunters and gatherers, and even horticulturalists, where the whole group works together to complete various tasks. In this case, the community is still working together, but the tasks are now divided up. Although these larger communities may sound ideal, with more people and more division comes more conflict. While nomadic groups are largely egalitarian, agricultural societies depend on hierarchy to provide order. Once populations grew and individuals gained more power, conflict was inevitable.

Archaeologists use residue analysis to find evidence of cultivated plants at large settlements, but there are many other signs in the archaeological record that can signal a reliance on agriculture. Typically large, permanent settlements that can host multiple families or generations are reliant on farmed crops. Evidence of permanent, large-scale structures, in addition to the presence of cultigens (like maize, beans, or squash) shows that people at these sites were investing in agriculture. There may also be evidence of the crops themselves in large fields, as well as the necessary irrigation systems that ancestral inhabitants used to water them. Other evidence of agricultural dependence can include signs of war in villages and nutritional deficiencies in ancestral remains.