Settlements

People create a range of spaces to harbor them at night, in inclement weather, and to do a number of activities. Many of us today are used to living in a single dwelling for years at a time, but we may also camp, forage for plants, or stay at a hotel on a trip. People in the past also created a range of short- and long-term solutions to shelter them under different conditions. Archaeologists call this the community’s settlement pattern.

Uncovering the types of settlements that ancestral peoples established helps anthropologists answer questions like:

- How big or small were community groups?

- Where did they live?

- How long did they live there?

- What did they eat?

- How did groups interact with one another?

- What relationships did people have with the land?

- Can we see relationships between peoples on the landscape?

Hunting Camp

Hunting camps are common in southeast New Mexico and we recognize them by their size. Small groups of nomadic hunters often set up temporary camps for a night or two along their route as they stalked herds of buffalo and other game. Because hunting camps were used for short periods and only by a small number of people, the chances of leaving things behind was very limited. In the archaeological record, hunting camps typically contain one or more fire pits and a few pieces of lithic debitage. These sites were left by ancestral nomads, who gathered around a fire and sharpened their tools to prepare for the next day’s hunt. Few other artifacts are present at these camps, as few other activities occurred here.

Some hunting camps were used multiple times, perhaps as groups returned regularly to a favorable spot. Evidence of repeated stays includes numerous fire pits, artifacts that date to different years, and multiple layers of cultural material. While archaeologists can identify when a camp was used over and over again, what we don’t know is why. It is possible that individuals remembered previous stops and traveled back, that knowledge of favorable camps was passed from generation to generation, that travelers used maps etched in stone to find these spots, or that groups simply stumbled upon a previously established camp and decided to stop again.

Residential Camp

Families or small groups established residential camps for longer, probably seasonal, time periods. At these sites, activities included cleaning animal hides, processing plant foods, making pottery and stone tools, and cooking for the family. Ancestral nomadic groups often set up these longer term settlements near a reliable water source. These spots were ideal not only for drinking, but they also attracted animals and enabled an abundance of plant life to grow. During the warmer months, families could carry out their daily tasks without worrying about moving around to find enough resources.

This more sedentary lifestyle leads to a more extensive archaeological record. Because more people are staying put in one spot for longer periods of time while carrying out various tasks, they tend to leave behind much bigger “footprints”. Archaeologists identify these sites by their extensive artifact scatters that include lithics, grinding stone, ceramics, fire cracked rocks, and even shell or turquoise. These sites also have features like storage and fire pits, but no permanent house structures. The absence of permanent homes still suggests that ancestral peoples were only staying here for parts of the year, not long enough to invest too much time building homes.

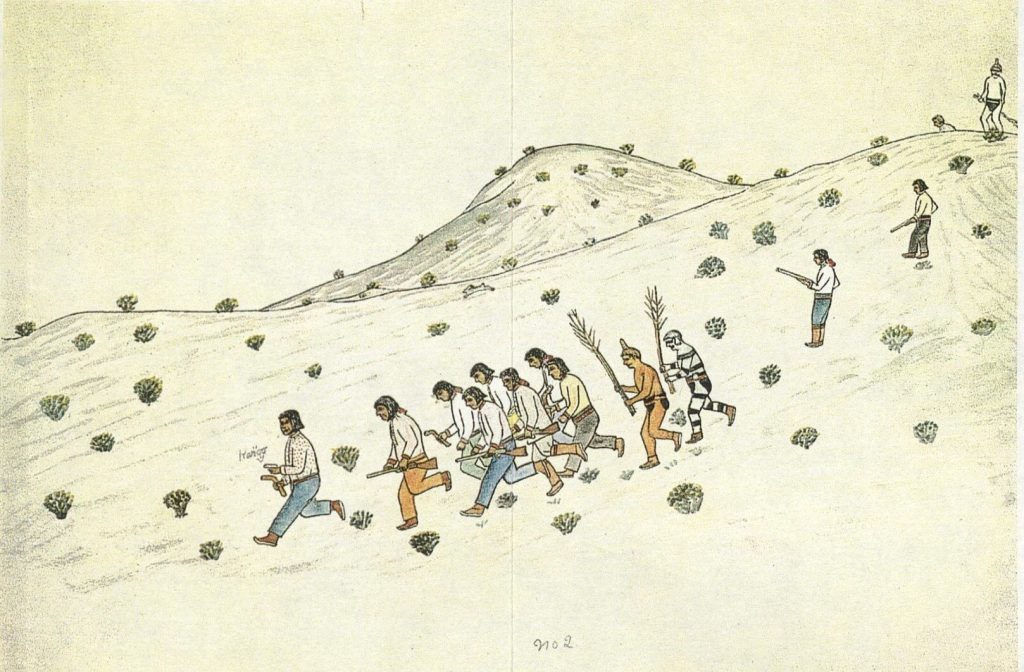

Although hunting camps and residential camps are distinct, the two site types were often created by the same people. Archaeologists believe that nomadic groups used a hunting technique called “tethered hunting”, in which small groups of hunters (1-3 people) would break away from the larger group settled at semi-permanent or permanent camps. These smaller breakaways would allow hunters to move quickly and unnoticed across the desert – hopefully resulting in a successful hunt. While they were away from the larger camp, these groups may have established hunting camps discussed above, or cave and rock shelter sites discussed below.

Village Site

Village sites are less common in southeast New Mexico and typically date to the late formative period. They have permanent architecture, including pit houses, kivas, and/or masonry room blocks. The investment in constructing villages is significant, leading archaeologists to believe that the residents lived at the site year-round. Additionally, village sites are typically much larger than hunting camps or settlement camps. The large amount of artifacts and features, coupled with evidence of multiple houses suggests that anywhere from several family units to hundreds of people lived in these communities. In order to support larger populations, villagers were often agricultural.

Some villages also acted as trade hubs. These trade hubs were places where communities could barter for food and goods unavailable in their own regions. When local groups were trading for food sources, we see non-local plants, animals, and minerals among their belongings. For instance, groups who subsisted mainly by hunting bison on the Plains may have traded with Pueblo peoples for their cultivated crops like corn, beans, and squash. The archaeological record at some villages also includes rare artifacts sourced from far away like copper bells from Mexico, Turquoise from around the Southwest, or shell from the Gulf of California. Finding these artifacts at village sites tells archaeologists that these populations were involved in significant trade networks.

Cave/Rock Shelter

Cave sites are particularly common in the Guadalupe Mountains, where ancestral peoples found refuge from the intense Chihuahuan Desert. Caves and rock shelters likely hosted an array of prehistoric activity, from hunters stopping for the night to shamans who practiced ceremonies. These cave sites also house rock art, including petroglyphs and pictographs, that have been shielded from damaging weather. Caves and rock overhangs that feature rock art are often associated with some variety of tobacco plant. While rock art can be found on many sandstone or volcanic walls, caves may have offered a unique setting for religious practices. In the darkness of these caves a flickering fire may have brought rock art to life.

Dry cave sites preserve organic matter for thousands of years. Artifacts like cordage, baskets, and sandals made of degradable plant material, wooden clubs or arrow shafts, even human coprolites preserve perfectly in some caves. This provides a unique opportunity to understand more about how people were using baskets, plants, and other fragile materials.